From a psychodynamic perspective, a specific form of self or identity dynamic is at the core of narcissistic pathology . This characterization applies not only to grandiose narcissists, but also to those in the vulnerable subtype, where grandiosity is cloaked in feelings of inferiority and deficiency. The specific pathology of identity formation that characterizes narcissistic personality disorder also lends itself to characteristic disruptions in interpersonal functioning.

On the one hand, individuals with narcissistic personality disorder often have a profound need for others to support their sense of self and also to help with self-esteem regulation. On the other hand, genuine engagement with others can threaten the stability of the grandiose sense of self, by confronting the individual with the painful reality that others have attributes that they lack. Nevertheless, maladaptive personality traits will be evident in many individuals seeking treatment for other mental disorders, such as anxiety, mood, or substance use. Many of the people with a substance use disorder will have antisocial personality traits; many of the people with mood disorder will have borderline personality traits.

The prevalence of personality disorders within clinical settings is estimated to be well above 50% . As many as 60% of inpatients within some clinical settings are diagnosed with borderline personality disorder . Antisocial personality disorder may be diagnosed in as many as 50% of inmates within a correctional setting (Hare et al., 2012). It is unclear why specific and explicit treatment manuals have not been developed for the other personality disorders. This may reflect a regrettable assumption that personality disorders are unresponsive to treatment. As noted earlier, each DSM-5 disorder is a heterogeneous constellation of maladaptive personality traits.

In fact, a person can meet diagnostic criteria for the antisocial, borderline, schizoid, schizotypal, narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders and yet have only one diagnostic criterion in common. For example, only five of nine features are necessary for the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder; therefore, two persons can meet criteria for this disorder and yet have only one feature in common. In addition, patients meeting diagnostic criteria for one personality disorder will often meet diagnostic criteria for another.

When it comes to treatments targeting narcissistic personality disorder per se, current treatment recommendations are based largely on clinical experience and theoretical formulations. Psychodynamic formulations have led to the proliferation of different treatment approaches, and case reports suggest that these treatments can be effective for some patients. Most influential have been those of Kernberg and Kohut , each of which focuses on clinical developments in the relationship between therapist and patient in long-term psychotherapy. Thus, for patients with narcissistic personality disorder, we recommend referral for empirically supported treatments for borderline personality disorder that have adaptations for narcissistic personality disorder. In particular, we recommend mentalization-based therapy , transference-focused psychotherapy (41–43), and schema-focused psychotherapy .

All three treatments target psychological capacities thought to underlie and organize descriptive features of narcissistic personality disorder. Dialectical behavioral therapy is an additional option for patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and significant self-destructive acting-out behaviors. All are longer-term treatments that require specialized training of practitioners. In their developmental considerations for the new DSM system Tackett and colleagues describe a life span perspective of personality pathology from early childhood to later life.

In spite of the reluctance of many clinicians to use the diagnosis before the age of 18, there is a constantly growing body of evidence that PDs can be diagnosed already in adolescence [4–6]. Personality pathology seems to be highest before the age of 20, with a decline of most of the pathological features over time . The diagnostic criteria of both, ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR, define personality disorders to begin in childhood or adolescence. If symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder are assessed already in early adolescence , the prevalence rate of BPD in an epidemiological sample of 11 year old children was 3.2%. Reliability, validity, and temporal stability of BPD-diagnoses in adolescents are similar to those in adulthood .

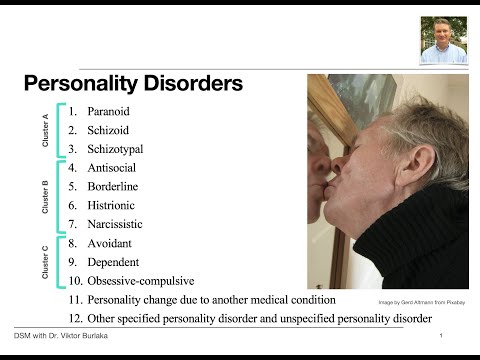

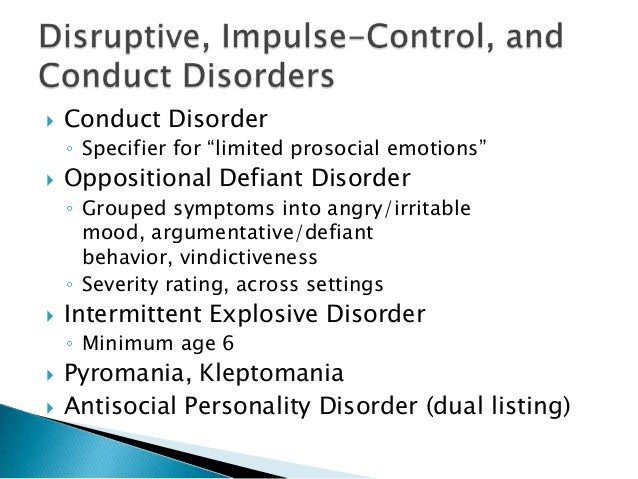

Personality disorders have been documented in approximately 9 percent of the general U.S. population. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and brief interventions designed for use by family physicians can improve the health of patients with these disorders. Cluster A includes schizoid, schizotypal, and paranoid personality disorders. Cluster B includes borderline, histrionic, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders.

Cluster C disorders are more prevalent and include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Many patients with personality disorders can be treated by family physicians. Patients with borderline personality disorder may benefit from the use of omega-3 fatty acids, second-generation antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers. Patients with antisocial personality disorder may benefit from the use of mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants.

Other therapeutic interventions include motivational interviewing and solution-based problem solving. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), provides a comprehensive framework for symptoms and classification of behavioral health conditions. However, efforts to make codependency a recognized disorder have been unsuccessful. The latest iteration of diagnostic criteria, the DSM-5, only includes dependent personality disorder as an official diagnosis, not codependency. The assessment of personality functioning goes back to the psychoanalytic concept of personality structure.

Kernberg was the first to combine the domains of identity, psychic defences, and reality testing to distinguish different levels of personality functioning or – in his terms – level of personality organization (i.e. neurotic, borderline, & psychotic). In Kernberg's view, the core pathology of patients with borderline and other severe personality disorders can be found in an impairment of their identity integration, what he called identity diffusion. Clinically, this state of identity diffusion leads to severe difficulties in describing oneself and others as well as problems in developing a sense of self with attitudes, interests, and life goals that are stable and reliable over time.

Another consequence of identity diffusion occurs in the realm of interpersonal relationships. Due to their fragmented representations of others, borderline patients are characterized by an impaired ability to mentalize, to empathize, and to build up and rely on stable relationships. Particularly intimate relationships are burdened by frequently changing self-states and either idealized or devaluated views of the partner . It is evident that all individuals have a personality, as indicated by their characteristic way of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others.

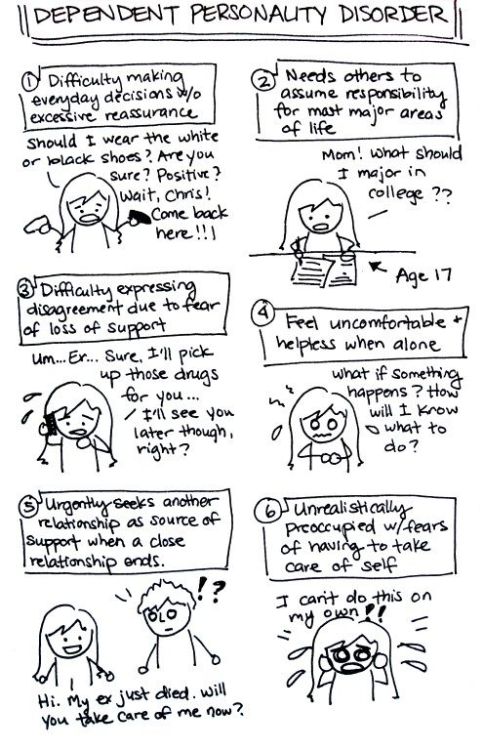

For some people, these traits result in a considerable degree of distress and/or impairment, constituting a personality disorder. People tend to seek interaction, connections, attachments, and relationships with other people. In fact, mental health is partly defined with regard to the strong emotional attachments to, and flexible interdependence on, close relationships we maintain with one another. But when interdependence becomes unbalanced to the degree that it is one-sided, it can become problematic, particularly if dependent personality disorder is involved. DPD can have a major impact on the ability to function in daily life.

For instance, society holds expectations regarding individual decisiveness, independence, and self-reliance that are dependent on age and situation, such as physical or medical issues. A person who does not meet those expectations could face difficulty functioning in school, work, and other interpersonal situations. The current study aims to improve knowledge about the relationship between pathological personality traits and their corresponding personality types.

The results point to some level of continuity between the two models when the variables were treated as dimensional. Contrariwise, there is a lack of strong scientific evidence to justify the maintenance of the categorical approach. We recommend the exclusion of the categorical approach from personality disorder diagnosis systems.

Each of the 10 DSM-5 (and DSM-IV-TR) personality disorders is a constellation of maladaptive personality traits, rather than just one particular personality trait (Lynam & Widiger, 2001). Antisocial personality disorder is, for the most part, a combination of traits from antagonism (e.g., dishonest, manipulative, exploitative, callous, and merciless) and low conscientiousness (e.g., irresponsible, immoral, lax, hedonistic, and rash). See the 1967 movie, Bonnie and Clyde, starring Warren Beatty, for a nice portrayal of someone with antisocial personality disorder. The grandiose, thick-skinned, overt subtype is characterized by overt grandiosity, attention seeking, entitlement, arrogance, and little observable anxiety. These individuals can be socially charming, despite being oblivious to the needs of others, and are interpersonally exploitative.

In contrast, the vulnerable, "fragile" or thin-skinned, covert subtype is inhibited, manifestly distressed, hypersensitive to the evaluations of others while chronically envious and evaluating themselves in relation to others. Interpersonally these individuals are often shy, outwardly self-effacing, and hypersensitive to slights, while harboring secret grandiosity. Many individuals with narcissistic personality disorder fluctuate between grandiose and depleted states, depending on life circumstances, while others may present with mixed features . Because of their high level of functioning, at first glance individuals in this group may not appear to have a personality disorder, and the narcissistic personality disorder diagnosis can be overlooked on diagnostic assessment. It is "a pervasive and excessive need to be taken care of that leads to submissive and clinging behavior and fears of separation, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts" (DSM-5). These symptoms give a picture of just how much destruction Dependent Personality Disorder can cause in an individual's life.

The disorder often introduces many personal and professional difficulties. Personally, people with the disorder have a hard time forming mutual relationships that do not becoming clingy or dependent. People with the disorder often do not have relationships outside of their family. Professionally, people with the disorder look for others to take care of them so they rarely take initiation—something that is essential in the professional world. In addition, the disorder raises people's risk of other mental illnesses, including other anxiety, depression, adjustment, and personality disorders.

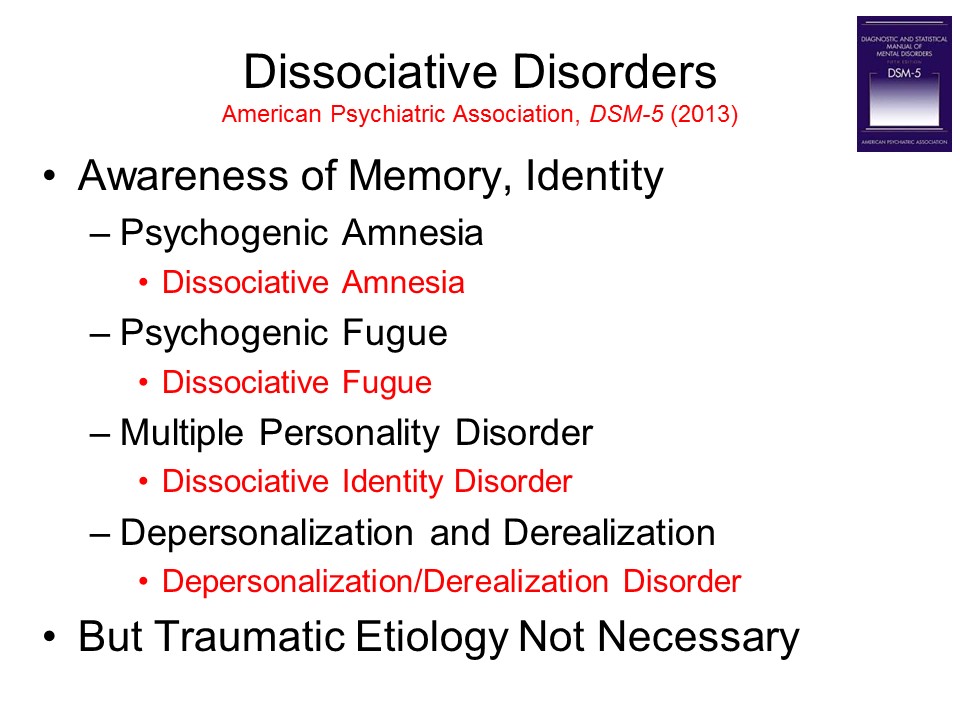

Even so, it appears that the majority of individuals with OCD do not have a pattern of behavior that meets criteria for this personality disorder. There may be an association between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and depressive and bipolar disorders and eating disorders. This issue is addressed to some degree in the alternative model for conceptualizing personality disorders developed by the DSM-5 Work Group and included in Section III of DSM-5. This model goes beyond the familiar focus on the descriptive features of different personality disorders to emphasize additionally the role of impairment of self and interpersonal functioning in personality pathology. Note that it is not the goal of this review to evaluate evidence for these other quadrants, but they are specified for completeness and are relevant to future empirical work that seeks to test the hypotheses generated by the STAR model (Fig. 1).

Certain types of psychotherapy are effective for treating personality disorders. During psychotherapy, an individual can gain insight and knowledge about the disorder and what is contributing to symptoms, and can talk about thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Psychotherapy can help a person understand the effects of their behavior on others and learn to manage or cope with symptoms and to reduce behaviors causing problems with functioning and relationships.

The type of treatment will depend on the specific personality disorder, how severe it is, and the individual's circumstances. The APA currently conceptualizes personality disorders as qualitatively distinct conditions; distinct from each other and from normal personality functioning. However, included within an appendix to DSM-5 is an alternative view that personality disorders are simply extreme and/or maladaptive variants of normal personality traits, as suggested herein.

Nevertheless, many leading personality disorder researchers do not hold this view (e.g., Gunderson, 2010; Hopwood, 2011; Shedler et al., 2010). At a lower level of functioning are patients like Mr. C, who present with comorbid borderline personality traits. In contrast to the higher-functioning group, these individuals exhibit a sense of self that is poorly defined and unstable; they frequently oscillate between pathological grandiosity and suicidality. In addition to demonstrating features of lower-level narcissistic pathology, Mr. C presents the challenge of vulnerable narcissism, appearing submissive and inadequate, but with a self-concept based on a covert sense of superiority.

The gap between an unrealistic and extremely fragile sense of self and objective reality leads to a lack of engagement in the world, as any meaningful contact with others challenges his covert grandiosity. Diagnostic confusion surrounding narcissistic personality disorder reflects the disorder's highly variable presentation and the wide range of severity that can characterize narcissistic pathology. Individuals with narcissistic personality disorder may be grandiose or self-loathing, extraverted or socially isolated, captains of industry or unable to maintain steady employment, model citizens or prone to antisocial activities. Given this heterogeneity, it is far from self-evident what such individuals could have in common to justify a shared diagnosis.

DSM-5 offers an alternative model of personality pathology that includes 25 traits. Although personality disorders are mostly treated with psychotherapy, the correspondence between DSM-5 traits and concepts in evidence-based psychotherapy has not yet been evaluated adequately. Suitably, schema therapy was developed for treating personality disorders, and it has achieved promising evidence. The authors examined associations between DSM-5 traits and schema therapy constructs in a mixed sample of 662 adults, including 312 clinical participants.

Associations were investigated in terms of factor loadings and regression coefficients in relation to five domains, followed by specific correlations among all constructs. The results indicated conceptually coherent associations, and 15 of 25 traits were strongly related to relevant schema therapy constructs. Conclusively, DSM-5 traits may be considered expressions of schema therapy constructs, which psychotherapists might take advantage of in terms of case formulation and targets of treatment. In turn, schema therapy constructs add theoretical understanding to DSM-5 traits. Cluster B personality disorders are characterized by dramatic, overly emotional or unpredictable thinking or behavior.

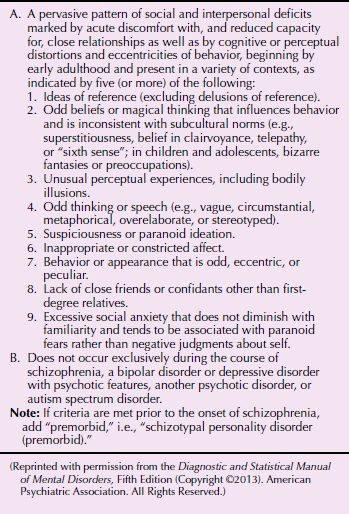

They include antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. Although hospitalization is sometimes necessary for the treatment of an Axis I disorder in individuals with dependent personality disorder, residential treatments are generally not indicated. Cluster A, characterized as odd or eccentric personalities, includes paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. Cluster B, characterized as dramatic, emotional, or erratic personalities, includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders. Cluster C disorders, characterized as anxious or fearful, are more prevalent and include avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. The changes that were intended to be made in the personality disorders diagnoses in comparison to DSM-IV were remarkable and covered many areas.

However, these changes have been moved to an appendix, the so called Section III of the DSM-5. The diagnosis of the girl in the first case vignette would be "dependent PD" in DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5. In the alternative model of the DSM-5 system there are four stages of assessment instead. First, it can be stated that the girl suffers from substantial personality impairment. Second, the level of impairment in self and interpersonal functioning is described as severe impairment in the four areas of identity, self-directedness, empathy and intimacy. This broad assessment gives a lot of information that characterizes the patient in much more detail and thus can give many hints for treatment planning.

A primary care doctor or mental health professional will ask you questions based on these criteria to determine the type of personality disorder. In order for a diagnosis to be made, the behaviors and feelings must be consistent across many life circumstances. Purpose of review The goal of the current paper is to review the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders , with particular focus on treatment of personality pathology. We briefly outline limitations of the traditional personality disorder diagnostic system, then, review differences between it and the AMPD, and how the alternative model can be applied for intervention planning.

Recent findings Criterion A of the AMPD refers to the level of self and interpersonal impairment and is required for establishing the presence of a personality disorder diagnosis. Criterion B characterizes the nature of that diagnosis by virtue of maladaptive personality traits. Both criteria have been positioned as having important treatment value, particularly when considered jointly. Several publications illustrate the utility of the AMPD for streamlining assessment, case conceptualization, and treatment.

Summary The diagnosis of personality disorder with the AMPD provides information with direct utility for case conceptualization and treatment planning. In addition, we highlight limitations in the literature related to the AMPD, with directions for future research aimed at improving understanding of the utility of the AMPD. We further situate our discussion of the AMPD within a broader scientific climate with focus on improvement of both personality and non-personality diagnosis, conceptualization, and treatment. This likelihood is especially prevalent for those individuals who also experience high interpersonal stress and poor social support.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.